Business Development in the Legal Industry

Revised 8/16/19

I recently sat down with Tom McMakin, co-author of How Clients Buy, to discuss reframing sales, our parallel approaches, and strategic missteps lawyers take that

- Undermine nearly all their client development efforts and

- Squander the majority of the money and time they’ve invested.

Tom McMakin: When we last spoke, Craig, you said that, among the four systemic obstacles we mention in the book, the most difficult one to overcome is unlearning what we already know about sales – from culture, film, and TV,

and from all the traditional, funnel-based, sales training tactics that work for products, but not necessarily for expert services.

We wrote that those tactics may be more detrimental to professionals’ sales success than helpful. You illustrate that in supporting your claim that what most lawyers (and most people) call sales is, in fact, a misguided application of marketing behavior to sales settings. Tell me what you mean by that.

Craig Levinson: The number of phenomenal – not great, but phenomenal – lawyers and law firms in the US and abroad is astounding. A General Counsel of a company, or any buyer of sophisticated legal services, doesn’t have the

time to meet with lawyers she doesn’t consider talented enough to do the job. If you secure such a meeting, and spend it telling her how great you and your firm are, you’re stuck in marketing mode.

Marketing is about being discovered, demonstrating thought leadership, and establishing credibility. A pitch outlining the extent of your talent; that’s just you continuing to substantiate your credibility. It speaks to a fundamental lack of understanding of the concept of professional selling and it hinders any progress towards you getting selected.

Tom: We’ll come back to that phrase, “Getting Selected,” but let’s first discuss how you define professional selling.

Craig: Professional selling is helping people and companies make sensible decisions that best serve their interests – even if one of those decisions is not hiring you. It’s you demonstrating your value, not telling me about it.

Professional selling is helping people and companies make sensible decisions that best serve their interests – even if one of those decisions is not hiring you.

Tom: Can you give us an example?

Craig: Sure, Tom. You were the COO of a multi-million-dollar company with numerous outside lawyers. I can only imagine what your e-mail inbox looked like. In a given day, on what percentage of new company issues, problems, and opportunities that came across the transom could you truly focus?

Tom: I don’t know. Five percent? Ten percent?

Craig: I would have guessed two percent, but let’s go with your gut: ten percent. You’re basically telling me that you placed ninety percent (90%) of those issues in your “someday” file – the accordion file of things you’ll tackle some-day. Correct?

Tom: I hadn’t thought about it that way, but, yes; I guess I did – and I still do.

Craig: Okay, let’s put a pin in that for a second.

Now imagine you meet a lawyer named Adam at a networking event and subsequently see him at other industry events. You and Adam always have compelling discussions about the challenges facing your business. He’s particularly conspicuous, however, in that he never tells you how great he and his firm are; he doesn’t bombard you with endless marketing materials singing his praises, and, most importantly, he never once pitches you for your business.

Tom: I’m finding that rather difficult to imagine, Craig.

Craig: I know. Call it suspension of disbelief.

Imagine all Adam does is question you about a few of those “someday” issues, providing perspective along the way, until you come to your own realization, on one of them, that the financial, tactical, operational, and personal impacts are greater than you ever imagined, and that you must deal with it now. He simply uses probing questions to help you gain the clarity to transfer an issue you placed in your “someday” file into your “today” file. What would be your assessment of Adam?

Tom: I’d find him to be extremely valuable. He’d also make a huge impression by not trying to get my business before we forged some sort of relationship. That’s so uncommon with lawyers that, by itself, it’s a differentiator.

You’ve reached a point where you’re seriously entertaining the idea of hiring Adam, and he still has yet to mention himself – the solution. It’s been all about you and your problem.

Craig: Valuable is the keyword here, Tom. I implore lawyers to find a way to provide VPE – Value Prior to the Engagement. Adam keeps providing you with value, and you just confirmed the impact it had on you. Now, might you consider hiring Adam to address that legal issue?

Tom: I would. Without Adam, I wouldn’t have appreciated the need to deal with the issue immediately. I’d actually be less inclined to use my current lawyers because of their failure to bring the issue to my attention.

Craig: In a nutshell, what Adam did is the essence of professional selling. It’s foreign to most lawyers because all they know is the traditional pitch-based “selling” that still runs rampant in Law, where the seller makes it all about the solution.

Notice that you’ve reached a point where you’re seriously entertaining the idea of hiring Adam, and he still has yet to mention himself – the solution. It’s been all about you and your problem.

Now, would this have the same impact in Management Consulting? I can’t say. Because Law was twenty-five years late to the marketing party and arguably fifty years late to professional sales, there’s no other expert service where the client development tactics are so universally outdated.

There’s a massive opportunity for the first “BigLaw” Chairperson who declares: “As of today, the pitching behavior is over. All we’re going to do is help people make smart, self-interested decisions that are 100% independent of our interests.”

Tom: I don’t know if that will ever happen, Craig, but it’s fascinating to contemplate. So, is that all there is to it?

Craig: Not quite. There are a few simple tactics one must use to get from that point to actually being hired, but except for handling one, completely avoidable, error that extinguishes more legal business than any other, the follow-up processes are largely academic. They’re custom-made for lawyers because everything revolves around questioning and challenging assumptions, which is what they do for a living.

Tom: Hold on a second. You threw out a pretty big caveat there. What’s this huge client killer you reference?

Craig: People forget how rare it is these days to have only one decision-maker in a company. There are often four or five executives who need to get aligned before a decision can be made.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen a lawyer like “Cary Smith.” Cary returns from a networking event, grinning ear-to-ear, saying, “I met this CEO who was very impressed with my experience in the aviation industry and the things I brought to her attention. She said I’d be perfect for their new deal with Odebrecht.” And then, nothing.

The CEO goes completely dark on Cary – she doesn’t return calls; she doesn’t reply to e-mails. Cary is left confounded, wondering what went wrong. I then have to tell Cary that, “After successfully using one of our professional processes to spark the CEO’s interest, you sent her back to the company to try and sell your services internally to the rest of the stakeholders. You sent an amateur to do the job of a professional.”

Cary needs to employ a simple, yet extremely subtle, method to maintain full control of the stakeholder process – one where Cary, not the CEO, is the person asking all those same impact questions to the remaining stakeholders.

Tom: One of the most thought-provoking things I’ve heard you say is that today’s top rainmakers don’t compete against other lawyers for business. You claim that they compete against inaction and that they preclude the

need for competition. How is that?

Craig: Let me make a distinction. I say today’s top rainmakers as a contrast to lawyers who built their practices over twenty years ago, when the demand for complex legal work still outweighed the supply of quality lawyers.

If you can engage executives on cutting edge business issues, before they recognize the need for legal assistance, you can often forestall the competitive tender process entirely.

Tom: That’s a universal obstacle – firm and company leaders who become blind to the fact that you can’t use the same tactics in a buyer’s market that you used successfully in a seller’s market. It’s a whole different ballgame.

Craig: So true, Tom. In terms of rainmakers not competing with their peers, think about what you stated earlier. Ninety percent of your new issues land in your “someday” file. Same with me. Same with virtually every prospect and client. If you’re a lawyer and that’s the case, why in the world would your main focus be competing against hundreds of firms for the work stemming from the acknowledged ten percent?

When you focus on problems and opportunities in prospects’ considerable “someday” files, it’s just you vs. inertia. I’ll take those odds any day of the week.

But that’s only half of it. Lawyers do this bizarre thing that I’ve never understood; they write and speak almost exclusively about the law. Most business people are so fixated on their business problems that they can’t focus on the intricacies of the law.

Here’s the reality: If you’re a lawyer whose articles keep summarizing new regulations or decisions, you’ll always be contending with time-consuming procurement battles where you’re competing against nine identical-looking lawyers and law firms – and often on price. I advise lawyers to write about future-looking business problems that mirror the conversations taking place within the C-suite, and not the same legal article that two thousand other lawyers are going to write. I teach them how to procure conversations with executives, at the front end of the problem management cycle, before business problems become legal problems.

If you can engage executives on cutting edge business issues, before they recognize the need for legal assistance, you can often forestall the competitive tender process entirely.

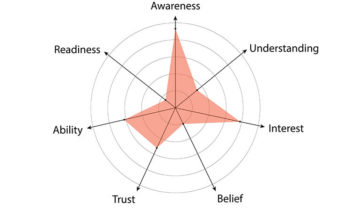

Tom: Let’s jump back to that term, “Getting Selected,” which you’ve used as a pseudonym for sales. Walt Shill, formerly of McKinsey and Accenture, said he didn’t think you can sell professional services; he thought you needed to help clients buy them. And our book is based on the idea of replacing the question, “What should salespeople do?” with “How do clients buy?” Although we expressed it differently, we all saw the need to reframe sales, not as something you do to clients, but rather as a process of engineering the optimal conditions to enable clients to buy.

Craig: I noticed that, too. We all put ourselves in the clients’ shoes and managed to find the same exact place from which to reverse engineer. We just took slightly different routes and developed slightly different vernaculars.

In your book, you discuss Design Thinking, which is what we three were doing – empathizing with our clients, seeking to understand them and their needs, and coming up with acceptable solutions to meet those needs.

In the law firm business development world, a few of us maintain an underground, informal “club” of instigators, futurists, and “apple cart up-setters.” We share information and we vent over the glacial pace of change in our industry. I’d venture that everyone in that group has been Design Thinking throughout their entire careers; they just didn’t know there was a term for it. It’s a group of consultants and pundits who all score incredibly high on the professional empathy scale and who view the world through very different lenses than do most people. You and your co-author Doug Fletcher would fit in perfectly.

Tom: That’s high praise, Craig. Thank you.

Let’s switch over to the marketing side of things. You make a claim that I hadn’t heard before. You say that most lawyers waste 95% of the true value of activities such as article writing and speaking engagements. How so?

Craig: The number one client development obstacle for most lawyers is unusually simple. They have no real justification to call on contacts and everything else they attempt comes off as a disguised sales pitch (because

it is) and they instinctively know how irritating prospects find that behavior. So a lot of them just stop trying.

The lawyers who truly “get it,” by contrast, see an article or a speaking engagement as an opportunity to solve that problem. They focus on the contacts with whom they can connect or reconnect before the article is submitted. These lawyers leverage articles and speaking engagements by using the quest for background information, quotes, and feedback as a plausible reason to routinely call prospective clients and referral sources.

Tom: But that’s not all; is it, Craig? You also say that 99% of networking is marketing, not selling, and that it’s far more effectively done at one’s desk than at a live event. You’re referring to these same marketing vehicles, right?

Craig: You’re correct, Tom. Lawyers mistakenly associate networking only with live events. And they network at these events using the same credibility-building behaviors that I defined earlier as marketing activities. Furthermore, the audiences at these networking events are a crapshoot.

For me, networking is about maintaining ongoing conversations with existing contacts and meeting additional, targeted contacts in a “non-salesy” fashion – whether it’s done live or virtually.

A shrewd rainmaker will use those same marketing vehicles, and the search for an assortment of viewpoints, as a plausible reason to ask the contact to whom he or she is speaking, “Who else knows this stuff backwards and forwards, who might be able to inform my article? Might I use your name in contacting them?” This results in referrals (solely for information) to two or three new contacts – who all just happen to be prospective clients and future referral sources for legal work.

Lawyers who then repeat this process with the new contacts to whom they’ve been referred, exponentially grow their networks in a short period of time. They not only get indirectly “vouched for” by the contacts who permit them to reference their names; they build the most prospect-rich networks possible, as every single contact they meet is, by design, an influential expert in the

respective target vertical where each lawyer wants to become well-known.

A lawyer who uses this process builds the most prospect-rich network possible, as every single contact he or she meets is, by design, an influential expert in the niche being targeted.

Tom: And how many new contacts can a lawyer obtain prior to an article being published?

Craig: It varies, depending upon the amount of time invested by the lawyer. On average, I’d say 20 to 40 new contacts per article or speech. I had one lawyer, however, who met 150 new, targeted industry contacts, over the phone, before we ever submitted his first article. Think about that.

In your book, you say that there are approximately 200 people who, if they knew who you were and used you on their matters, would keep you busy for the rest of your life. Imagine getting intimately known by three-quarters of those people during the authoring of your first article. It’s pretty staggering.

You would think every lawyer would be jumping at the chance to implement this process. It costs nothing. It shaves off hundreds of networking hours each year. Lawyers are completely comfortable with it; prospects and clients welcome it with open arms, and the results are career-altering. Despite the fact that this method eliminates virtually all the business development obstacles (actual or perceived) that plague lawyers, only a tiny percentage of them ever even attempt it.

Craig Levinson, Esq.

Craig Levinson, Esq.

Craig is an award-winning legal client development consultant. He’s the owner of Levity Partners in Miami, Florida.