How Selling Expert Services is Different

Notwithstanding the intuitive appeal to me of the distinctiveness of selling expert services, I was initially skeptical. After all, Tom sells expert services (as do I). It’s self-serving to declare the process of selling expert services somehow special. Nevertheless, I’m persuaded by Tom’s logic:

Selling expert services is different in the sense that expert services are sold on reputation or referral or relationships, not like goods which are sold on features and attributes.

Furthermore, I believe the consequences of failing to act upon the implications of Tom’s insight are likely to become increasingly catastrophic.

What Are Expert Services?

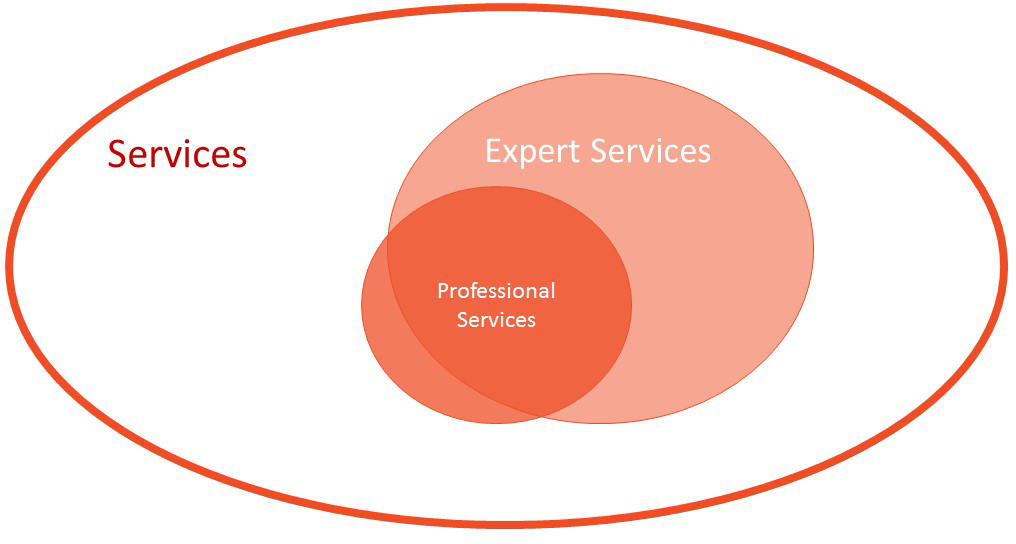

Before we proceed, let’s agree on a definition. A service is defined as an act of helping or doing work for someone. Services encompass everything from TaskRabbit to the work done at the Mayo Clinic. Tom is interested in a narrower scope differentiated by expertise, the application of which yields results vastly superior to those obtained by the majority of the population.

Expert services include, but are not limited to, most professional services.

Expert services include, but are not limited to, what we know as professional services that typically require certification (e.g. lawyers, architects, and auditors). Of course, the requirement for a license or certificate is no guarantee of expertise. Instead of ensuring expertise, licensure may instead serve to limit competition. In other words, expert services are a subset of services that includes, but is more encompassing than, most professional services.

For example, Marko Djuk is the artist who created the illustration of Tom embedded below. Marko is a purveyor of expert services, as his artwork is vastly superior to that which might be produced by the majority of the population.

Marketing Physics

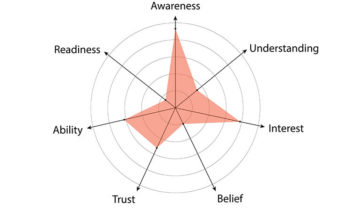

In order to understand how marketing expert services is different, let me introduce Doug Hall’s “marketing physics” framework. Doug’s framework clarifies the elements of an effective value proposition:

While a clear statement of the benefit of an expert service is necessary, it’s insufficient. In fact, Hall’s data indicates the more powerful the statement of benefit, the greater the requirement for real reason to believe.

Per Hall, there are five strategies for conveying reason to believe:

Kitchen logic — explains how the promised benefit is delivered using language to which prospective customers can easily understand and relate.

Personal experience — is about providing the opportunity to see, feel, and experience the benefit of your product or service.

Pedigree — is about providing confidence by detailing the development and marketing heritage behind your product or service. A well-established brand is a source of pedigree.

Testimonials — can be from customers, acknowledged experts, or independent third parties.

Guarantee — can provide a powerful reason to believe, if inclusive and credible.

To some degree, each of the preceding is a substitute for another. Testimonials, for instance, might overcome a lack of personal experience. Furthermore, different products and services are amenable to different combinations of sources of reason to believe.

Product Features and Kitchen Logic

When Tom asserts that products tend to be sold on features, I hear that he’s suggesting that product marketers tend to emphasize kitchen logic in their sales strategies. For example, consider the following advertisement for the iPhone 7 by Apple. It makes a kitchen logic link between features and claimed benefits:

It makes the things you do with your iPhone better, faster, and more powerful.

The advertisement enumerates features — new camera systems, stereo speakers, and “the most powerful chip ever in a smartphone” — to explain how the new phone is going to be “better, faster, and more powerful.”

Of course, the accumulation of positive consumer experiences that constitutes the overarching Apple brand is also a powerful source of reason to believe. The point, though, is kitchen logic links product features with the claimed benefit. Kitchen logic tends to be a primary source of reason to believe for products.

Logical Disconnects Around the Kitchen Table

Arguably, the “features” of expertise are more difficult to convey in a readily understandable and persuasive manner. The iPhone 7’s kitchen logic is compelling:

“The most powerful chip ever in a smartphone” → “faster and more powerful”

In contrast, I find it difficult to formulate a concise explanation of how my studies of system dynamics, complex adaptive systems, and real options theory translate into a differentiated capacity to advise burgeoning e-commerce businesses on strategy. I believe it to be true, but a concise statement of cause and effect eludes me.

The (Relative) Diminishment of Brand

In the world of management consulting, there are few firms with brands as well known and highly regarded as McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group, Bain, and Oliver Wyman. The pedigree conveyed by having such a brand on one’s business card is significant. Even so, the world seems to be shifting to the detriment of brands.

Consultants at these firms are likely to be students of the moral and political philosopher, Adam Smith, who wrote in Wealth of Nations:

As it is the power of exchanging that gives occasion to the division of labour, so the extent of this division must always be limited by the extent of that power, or, in other words, by the extent of the market. When the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment, for want of the power to exchange all that surplus part of the product of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the product of other men’s labour as he has occasion for.

As Smith would have anticipated, transportation and communications technologies have shrunk the world, enlarged potential markets for expert services, and encouraged specialization. As a consequence, the relative value of general service brands is diminishing.

Consider the small, London-based firm of Strategy Dynamics. In the domain of quantitative, dynamic modeling of strategic processes, Kim Warren’s firm can go toe-to-toe with any of the strategy powerhouses — even without the brand pedigree recognized by the general business audience.

What’s Left for Expert Service Providers?

If kitchen logic is evasive for highly specialized service providers and the power of pedigree diminishing in the face of market fragmentation, what’s left for a seller of expert services? Let’s set aside guarantees in this context for another day.

Tom might say there are two viable strategies for communicating differentiated levels of reason to believe:

Personal experience — which includes all types of trials and sampling

Testimonials — including referrals by, and testimonials from, past clients

As Tom puts it:

You don’t talk about your expertise, you demonstrate your expertise.

Of course, that’s what content marketing is meant to address. Writing books, whitepapers, and articles create the potential for a form of sampling. So do podcasts, webinars, and videos. They are mechanisms through which one can demonstrate expertise prior to the sale. Strategy Dynamics, for example, offers a wide array of free resources on its website. Relatedly, the techniques associated with sharing digital content are designed to encourage referrals and other casual forms of testimonials.

Effective sales techniques aren’t limited to digital content. More than ever, carefully selected and executed talks and conversations are means by which expertise can be demonstrated.

In short, I believe Tom’s assertion is fundamentally correct. Selling expert services is different. Product firms can more readily draw upon kitchen logic to persuasively link features with claimed benefits. Furthermore, I suspect that product brands may be more resistant to erosion by specialization and market fragmentation than are service brands. By process of elimination, sellers of expert services must become masters at providing real reason to believe in the value of their respective offerings through personal experience and testimonials.

The Consequences of Failure

If we fail to heed Tom’s message, we risk the commodification of our service offerings. The emergence of platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, Uber, Fiverr, and a host of others make the consequence of commodification clear. Even on more supplier-friendly platforms such as Uber and Etsy, it’s damned tough to make a living unless your value proposition is compelling. In a world that already has LinkedIn, PrestoExperts, and Maven, how long will it be before the scope of your expert services domain becomes uncomfortably broad and undifferentiated?