Does Specialization Undermine Clients’ Understanding of and Respect for Your Work?

Do you know what an endovascular surgical radiologist does? Neither did I until I started writing this article. However, if you’d been diagnosed with a cerebral arteriovenous malformation, you might want to learn. The rest of us are usually content to remain blissfully ignorant of the function and capabilities of such specialists. That might be a problem.

The Compelling Push to Specialize

We providers of expert services are increasingly compelled to specialize. Tom McMakin calls it “shrinking the pond.” In Memo to Expert Service Providers: Carve Yourself a Niche, Tom writes:

Consultants and professional service providers would do well to heed this lesson at a time when they’re swimming in an ever-expanding pond of similar firms. There are an estimated 700,000 business consulting firms globally, and many of their services are fast becoming commodities.

Luk Smeyers of The Visible Authority piles on in Want to be a Furiously Successful Consultant? Put All Your Eggs in One Basket:

But if you want to be an insanely successful consultant— the kind of success most consultants will most likely never experience — you need to put all your eggs in one basket.

I’ve often sung from the same hymnal:

I think Tom and Luk are right. We must specialize in order to offer clients truly differentiated value. If we fail to do so, we risk becoming commodities.

Specialization and Understanding

Being an expert means we have a high level of relative expertise. The gap between our expertise and that of our prospective clients creates the potential for us to add value. That’s the good news.

The bad news is a gap in relative expertise makes it difficult for prospective clients to understand what we do. As Adam Grant notes in Think Again:

When we lack the knowledge and skills to achieve excellence, we sometimes lack the knowledge and skills to judge excellence.

Even when we’re aware of the endovascular surgical radiologist who lives down the street, we may not understand what she does, much less how she might help us.

Understanding and Respect

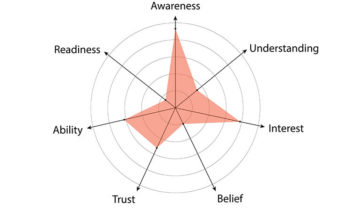

In How Clients Buy, Tom and Doug Fletcher presented the Seven Elements—a strategic business development recipe that describes the ingredients necessary for prospective clients to buy your professional or expert services:

- A prospective client must be aware of you.

- A prospect must understand what you do and how you can help them.

- In order to engender sufficient interest, your capabilities must address your prospective client’s priorities.

- A prospect must respect your work and believe you can do the job.

- A prospective client must trust that you will have their best interests at heart.

- A prospect must have the authority and ability to engage.

- The timing must be right. That is, a prospect must be ready.

Although Tom and Doug present the Seven Elements as a “MECE” list (mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive), I’m not so sure. Given Adam’s observation, I suspect there is a relationship between understanding and respect. That is, when we have low levels of expertise, we don’t always know what expertise looks like. If our understanding of a specialty is low, so too might be our level of respect for the work of the specialist.

Testing My Hypothesis

The world of consulting and expert services is becoming increasingly specialized. I suspect that may be driving down prospective clients’ understanding of and respect for us specialists’ work. (Complex systems are rife with such balancing feedback.) If only there were a way I might test my hypothesis.

Well, maybe there is.

Between mid-November 2020 and mid-March 2021, 107 people completed the Seven Elements Assessment. For the most part, they were specialist practitioners in small-ish firms.

The assessment consists of a series of statements to which one is asked to respond using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The responses generate scores associated with each of the Seven Elements.

- A high score indicates the respondent perceives the associated element to be a relative strength of their organization.

- A low score represents a relative weakness and challenge and, thus, an opportunity for improvement.

If my hypothesis has any merit, we would expect to see relatively low scores for Understanding and Respect. In fact, that is the case:

| Element | Average Score |

| Awareness | 2.9 |

| Understanding | 2.9 |

| Interest | 3.5 |

| Respect | 2.9 |

| Trust | 4.0 |

| Ability | 3.2 |

| Readiness | 3.1 |

In other words, over 100 specialist practitioners, on average, perceive Understanding and Respect on the part of their prospective clients to be a relative shortcoming.

The assessment was designed primarily to stimulate self-reflection and conversation. Its results don’t represent rigorous research. Nevertheless, I think the results are provocative and probably better than simply guessing about the relationship among specialization, understanding, and respect.

Implications and Opportunities

When I think of business development, my thinking tends to default to questions about building awareness, cultivating trust, and developing relationships with contacts who have the authority and ability to engage. I wonder, though if I’ve been giving the dimensions of understanding and respect short shrift? What if the pressure to specialize is likely to drive down prospective clients’ understanding of and, potentially, respect for what we do?

What might we do about it? At least three courses of action come to mind.

Spend More Time with Fewer Prospects

The relationship between market focus and understanding is complex. In Trust and the Paradox of Market Focus, I note how specialization can allow you to spend more time with a shorter list of prospects. That, in turn, can help you build their understanding of and respect for your work.

Cultivate Referrals

How Selling Expert Services is Different explains why Tom and Doug emphasize that referrals continue to be crucial to developing new expert services business. After all, if you are unfortunate enough to be diagnosed with cerebral arteriovenous malformations you are most likely to be referred to an endovascular surgical neuroradiologist by someone having an intermediate level of relative expertise. Strictly speaking, you don’t have to know what the specialist does as long as a trusted, knowledgeable third party vouches for the value of the specialist’s skills and relevance.

Share Your Expertise Generously to Educate Prospective Clients

Luk would probably encourage you to generously share your specialist expertise in the form of digitally distributed content. In other words, close the expertise gap by educating prospective clients regarding your skills and relevance. Prospective clients just need to understand enough to allow them to more accurately assess and respect your work.

What do you think? How do you help prospective clients understand your specialized work to the point they can appropriately value your skill and relevance?